135 years ago, a priest and composer Viktor Matiuk took the throne of the Kariv church for the first time

The arrival of Father Viktor Matiuk in the village was strange. The books and other writings that the priest brought with him were commonplace for the villagers, but a large black instrument that required more manly strength to carry to the resting place was something special, and had never been seen in the village. Later on, the people of Kariv would feel the magical power of that instrument, when the magical melodious sounds of their native song would mysteriously come out of its deep interior, pleasing the human ear.

The composer arrived in Kariv at the height of his creative powers. At that time, his famous “Vesnivka” was already being performed by O. Myshuga all over Europe, his works of various genres were being performed at festive events in Lviv, new music books were being prepared for publication, and meanwhile the composer, by some gesture of fate, found himself far from the noisy, crowded centers in a quiet Galician village.

First of all, as a parish priest, Father Viktor tries to get to know the village, the community, over which he is now entrusted with spiritual care, to lead it along the difficult path of spiritual and cultural revival. The newly built church made a good impression on him. So there is a wide field for his activity here as well.

But let’s go back to the time when the composer lived and worked. Back then, Galicia was taking its first steps toward national revival. Serfdom had already been abolished, but the Galician people continued to be under social and national oppression. Having neither its own state nor any social organizations, it was difficult to raise the people to national self-affirmation.

According to the composer, the Ukrainian people were languishing under oppression and captivity, their native language and song were in disgrace, and only the ordinary Ukrainian people “hid and passed from mouth to mouth those most precious treasures as a legacy of their ancestors.” So, as we can see, the state of Ukrainian society at that time was still depressed.

The centuries-long Polish rule over Galicia, which suppressed its national development, was somewhat weakened by the arrival of Austrian rule with its constitutional monarchy and general ideology of enlightenment. It was a favorable time for Galicia’s national revival.

This was also facilitated by the European national liberation movements, the “Spring of Nations.” And in such geopolitical circumstances, a whole cohort of leading cultural figures, awakeners of the national spirit, starting with the “Russian Trinity” (M. Shashkevych, J. Holovatsky, I. Vahylevych), appeared on the scene of Galicia, and in increasing numbers. Subsequently, the priest and composer Viktor Matiuk entered this arena, covering a wide range of activities in his creative, priestly, and public work.

The nineteenth century was significantly saturated with political movements, internal political and religious confrontations. Due to further assimilationist pressure from the Polish side, a significant part of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, mainly the clergy, switched to Polish cultural and linguistic communication, often practicing it in churches. Let us recall the public response to the sermon in Ukrainian by Fr.

On the other hand, Galicia at that time was overrun by the so-called Muscophilia, which spread throughout western Ukraine (Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia). This religious and propaganda movement aimed to turn Galicians into Russians. Being financially supported by Russian official circles, Muscophilism found considerable support among the clergy and other segments of society. Their “Kachkovsky reading rooms” were distributed on a par with Prosvita.

But the flame of the awakened national revival could no longer be extinguished by forces hostile to Ukraine.

In Galician society, a new progressive force began to enter the arena of national revival – the secular intelligentsia, which was joined by a certain cohort of priests, including composers: I. Lavrivsky, M. Verbytsky, P. Bazhansky, V. Matiuk, S. Vorobkevych, and others. In the conditions of the absorption of Ukrainian culture by the then dominant Polish culture, realizing that the Ukrainian church, fulfilling only its canonical prescriptions (and Galicians are overwhelmingly zealous confessors), does not give the nation a full-blooded breath, it declines, assimilates, and the Galician, against the background of such purely religious devotion, looks like something secondary, humiliated. And so these companions of the national revival managed to find a way to the heart of the Galician, to his spiritual affirmation, instilling in the official Galician religious consciousness a national cultural current that became the driving force of the Ukrainian revival in Galicia.

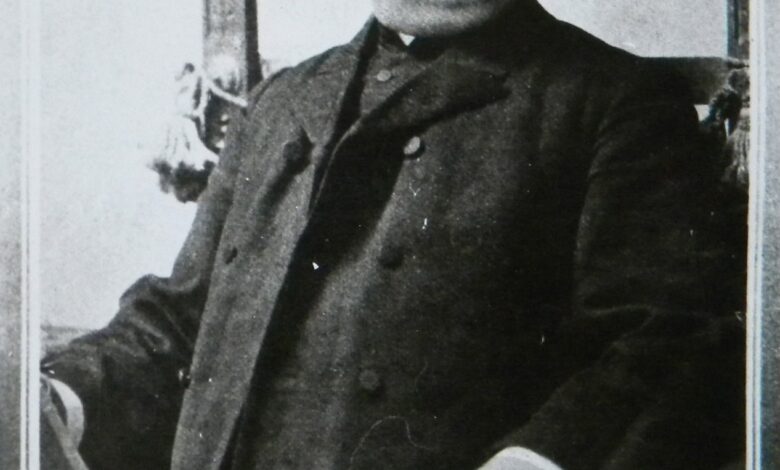

It was among this cohort that Father Viktor Matiuk (1852-1912), a composer, active public and cultural figure, whose creative and social activities can serve as an example of the skillful inculcation of folk spiritual treasures into church practice and the revival of Ukrainian identity on this basis.

Viktor Matiuk’s creative and social activities are quite extensive, including musical arrangements of folk songs, organization of folk choirs, publication of the first voluminous song collection in Galicia, Boyan, creation of educational music books and other collections of folk songs and musical works. All of this was actively implemented in the life of Galician society, injecting a powerful stream of national ideas into the church life of Galicians, thus creating a kind of spiritual phenomenon-the Ukrainian Church.

In Kariv, along with his pastoral work, the father is actively engaged in secular and social work, raising the cultural level of his parishioners. One of his important activities was the creation of a choir and its professionalization, which allowed it to perform on the Lviv stage.

To revive national traditions, such as the cheerful, cheerful Easter vesnianky of the eiderdowns (called “Holubka” in Kariv), the father engages his children, stirring up all the surrounding villages, where these traditions had already fallen into decline, with these crowded rituals. These Easter vespers in Kariv survive to this day, but such a crowded event, when the entire village, from children to the elderly, gathered in a large song circle, unfortunately, has remained only a painful memory.

When the Prosvita Society was organized at the beginning of the last century, Viktor Matiuk became its first chairman. It should also be said that Father Matiuk was also engaged in medical treatment, having skills and knowledge of herbal medicine.

In parallel with his work, he composed church and secular music, published music collections, and music textbooks for Ukrainian schools. After collecting works by I. Lavrivskyi, M. Verbytskyi, P. Bazhanskyi, and his own, he publishes a collection of songs for the Boyan men’s choir at his own expense.

Such is the wide field of activity of the priest-composer, a devoted, sacrificial activity, for he often gave his money (and in large amounts) to publishing and popularizing musical literature among the people.

Do we have many such sacrificers among the priesthood today?

In this way, among a whole galaxy of composers, writers, artists, and other cultural figures, Viktor Matiuk paved the way for Ukrainian souls, awakening their civic and national dignity to the point that in the first decades of the 20th century Galicia turned from a humiliated, oppressed nation into an equal nation capable of fighting and defending its statehood and its place under the sun. This is the power of the native word, native song, and native tradition.

As you ponder the figure of Viktor Matiuk and other leading priests of that time who awakened the spirit of the people, you wonder: what hand of God led them on this path? Like other priests who lived before them and after them, they could have lived quietly, earning their bread and butter, following church regulations and canons. But in this case, what would have happened to the Ukrainian people today? These ascetics of the Spirit comprehended with their spiritual nature the understanding that there is something higher in church activity than ordinary canonical prescriptions: it is care for the Lord’s Spirit that lives in the people and by which the people live, and that it is this Spirit that must be cherished most, because this Spirit is the Ukrainian nation and the Ukrainian church, and in its entirety, Ukrainian culture.

That’s why they raised to heaven, along with the canonical chants, the folk song. “Holy God,” “Native Land,” and “How the Night Will Cover Me” are all spiritual values of the same magnitude, because they elevate a person to a higher spiritual level, cherishing those highest human feelings-love for one’s neighbor, for Ukraine, for God.

The composer ended his earthly journey in the village of Kariv on April 8, 1912, on Easter Monday, and was buried there, where a majestic monument by the famous Ukrainian sculptors A. Koverko and A. Pavloso stands above his grave. It is on Easter Monday that the people of Kariv always honor the memory of the composer.

Stepan Ivaseiko.